|

I am by no means an expert: I completed my first public art project in 2018, installed my second in March 2022, and am currently trying to decide whether or not to pursue a third. While I have not found public art particularly lucrative or easy, it has certainly been a catalyst for growth and learning. The following are some things I’ve learned about dealing with the conceptual, emotional, and logistical challenges of public art—things I wish I’d learned sooner and hope not to forget.

YOU WANT IT: Pursuing a Public Art Project Join the Roster Many cities maintain a “roster” of artists who have been pre-approved as suitable candidates for public art commissions, and if you are even tentatively interested in public art, there’s no reason not to apply for a roster. Roster inclusion doesn’t guarantee anything, but there’s a good chance you’ll receive targeted announcements about upcoming opportunities, if you’re a good fit for a project with a tight deadline, you might be specifically recruited to apply. Perform a SWOT Analysis SWOT is a classic career development exercise in which you take inventory of your strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Tailoring the same analysis to your public art dreams can guide you towards projects that are a good fit for your approach and your circumstances. As an example, here’s what my own SWOT might have looked like just prior to my first public art project: Strengths: designs integrating nature and culture, interviews and historical research, community engagement, thinking of things that could go wrong, willing to work hard and learn new processes Weaknesses: not prior public art experience, not much $ to put in up front, no car, not physically able to wrestle large/heavy items, getting hung up thinking of things that could go wrong, no studio space of my own Opportunities: Seattle has many public art opportunities, inclusion in roster of artists pre-approved for public art proposals, potential to use studio space at work during off hours, friends good at moving large/heavy items Threats: liability issues, public art has to last at least 30 years, outdoor work is vulnerable to weather and vandalism, public art would need to fit around my FT work schedule, working outdoors in unpredictable conditions Do the Math Not all commissioning agencies set public artists up for success. Read the call for application carefully: if they are asking for the moon but their budget would barely cover a Moon Pie, it’s probably not worth your time to even apply. Budget ≠ Profit A big budget is seductive; it can be hard not to fantasize about seeing that money in your very own checking account. But even when a project is big and shiny and successful, the artist only ever pockets a percentage of the budget—at best. Bigger budgets come with bigger potential for profit, but also for loss. I Spy Notice every piece of public art and really look at it. Consider what you do and don’t like about it, of course, but don’t stop there: how is it made? What materials and techniques were chosen and why? How is it held up or down? What has worked well? What hasn’t? How old is it? Does it look its age? Then get just as curious about things that aren’t artwork: how do flagpoles work? How are drinking fountains attached to the ground? What kind of aggregate crumbles the worst, and what kind of internal structure can you see inside? Some of this research will be only of passing interest, but other items will be invaluable when it comes time to make your own work. YOU’VE GOT IT: Woo hoo! You’ve been commissioned! Now what? Big Words and Fine Print Read the contract. Read ALL the words in the contract. Have someone else read the contract (in Washington I had all my contracts reviewed by WA Lawyers for the Arts at $20 per consult; your state probably has something similar). Follow up on any terms or concepts you don’t fully understand. Ask about anything you don’t totally agree with—but realize that many large agencies will not make changes to their contracts. Make a list of any actions you need to take to remain in compliance with the contract that are not part of your usual M.0. (For example, giving the agency a change of address if you move). Prepare for Pushback Even once you’ve gotten the commission, you will still experience rejection. Some project stakeholders may feel that the project is being imposed on them; they might express this openly (“This is a waste of money.”) or more subtly, by being slow to respond or difficult to work with. Some people will be onboard with the general idea but disagree with your design decisions. Don’t take any of this personally! Listen with respect and an open mind, but remember that it may not be possible to make everyone happy. Let Go a Little Public art is not your art. Compared with your usual, personal creative process, the process of creating public art will probably not feel the same or flow in the same way. I trick myself “public art” out loud, but the term I use in my head is “public project.” For me, “project” bears fewer assumptions and expectations than “art.” YOU’VE GOT TO DO IT: Making a Big Job More Manageable Preload the Paperwork Set up all the paperwork for the entire project with blanks to be filled in as you go, and list each form or deliverable on a timeline or calendar, adjusting as needed. I find it’s easier to jump through bureaucratic hoops if I get them nicely lined up before they’re set on fire. Start From the End In language learning, there’s a great tool called backchaining; when you’re stumbling over a complicated word or phrase, you sound it out syllable by syllable starting from the end of the word. For example, one of the neighborhoods where I used to teach in Tokyo was called Seisekisakuragaoka: phew! Backchaining would break this snarl of sounds down like so:

In actuality, I didn’t think of this approach until it was too late for my most recent project. By starting at the beginning, I was constantly creating problems and then having to solve them. I ended up with sculptures too big to fit on a standard pallet and a crate too big to fit out my studio door or in through the site door! Backchaining my decisions would have saved me time, money, and stress.

0 Comments

About a decade ago I asked one of my favorite former professors to write a letter of recommendation for an application I was really excited about…and he refused.

“I don’t know you well enough,” he explained before driving the dagger a little deeper: “…and that’s your fault.” I felt slapped. This was a dude I’d studied with for two years, with whom I’d laughed, cried, danced, drunk two-buck Chuck, and had conversations that continue to shape the work I make today, and he didn’t know me?? But then I realized that he had a point. We hadn’t really spent time together since I graduated, mostly by my choice. Post-school I was depressed, stressed, and a mess; I figured I was shielding the people I cared about by avoiding them. I had continued to have valuable conversations with him, but entirely in my own head; oddly enough, he was unaware of these imaginary interactions. His refusal still stings, but more in a tough love, snap-out-it kind of way. It also helped me to realize that the process of securing recommendations is excellent practice for developing and maintaining good relationships of all kinds. Yes, you have to plant the seed, but you’ve also got to keep it fed and watered and weeded if you hope to come back and pick some fruit. At its best, a recommendation reflects a relationship. The process of securing a strong recommendation starts earlier and lasts longer than you might assume.

Is this a lot of work? Good heavens, yes! Do letters of recommendation really matter? Not always. But let’s imagine you’ve written a bang-up proposal and are neck-in-neck with another strong applicant: suddenly your supporting materials start to carry more weight. A recommendation that’s substantive, detailed, personal, and enthusiastic can nudge your application over the finish line. Even more importantly, the recommendation process can create wins from failures. Remember I suggested that your recommender should be a person you like and respect? That’s what makes the recommendation process itself a means of growing your community and making professional progress. Even if an application is rejected, your recommender knows that you went for it and their minds have already started to test-fit you for similar opportunities. Ultimately, a good recommender holds a stake in your growth and success. Since the first session of my Cultivating Creative Expression class way back in August, the students and I have had several regular and ongoing assignments. Just like physical exercise or daily vitamins, these assignments aim to build and maintain vitality, resiliency, and full range of (e)motion:

Daily Diary (all day, every day—at least ideally) It can seem as if creativity strikes like a bolt out of the blue, and sure, sometimes it does, but a more reliable source of inspiration is the world around you. There are two essential steps for harvesting the gold nuggets littering the ground at your feet: you have to spot them and then you have to actually pick them up! And by “pick them up” I mean write them down: trusting your memory to hang onto a good idea is like leaving a gold nugget on the ground for later. I had the students use Lynda Barry’s fantastic framework for a daily diary (please read more about it in the maestra’s own words). There is so much to love in this format:

Final note: because this was an assignment, and because students are students, there were several instances where people missed a few days (or weeks) and then tried to go back and fill them in later. THIS DOES NOT WORK. As I put it to one of my sporty students: imagine you skipped the gym for 6 days; would it make sense to go in on the seventh day and cram a week’s worth of workouts? This journal exercise is about building creative muscle through regular and repetitive use. If you stop, start again wherever you happen to be. Off-Leash Hour (minimum one hour per week) I couldn’t think of any better image to illustrate this assignment than dogs at a dog park. Picture that moment when the leash is unclipped and the dog bursts like a firework into joyous action. Leash-on versus leash-off, he might seem like an entirely different dog; I suspect that the leash-off version is closer to the dog’s true self. The off-leash hour is your time to do something, anything (ok, sure, anything not criminal or immoral) that makes joy come out of your pores. No judgment: whether it’s a video game, a long bath, a session of Ukrainian egg-decorating, or running figure-8s at the dog park, it’s valid. Extra credit if your off-leash activity takes you outdoors. I think that this practice has the potential to reconnect us with that playful, unselfconscious inner child that so many of us have paved over as adults. An hour of joyful freedom is like a taste-test, a sample of what it can feel like to genuinely invest in a creative practice. Giving (minimum one hour per month) Although I can argue for days that being actively creative is fundamentally about offering your best gifts to the world, and is therefore a generous and healing practice that effectively lifts all boats, the word on the street can say otherwise. Perhaps you’ve heard that creative pursuits are frivolous, or wasteful, or selfish? Maybe you’ve even taken these ideas onboard. In the long run it’s best to shove these unwelcome untruths out of your boat, but in the meantime let’s balance them out by dedicating some time to someone other than yourself. I’ve loved hearing about the things my students have done with their monthly giving hour. One of them noticed a elderly neighbor’s yard getting out of hand and stepped in to help out. Another started to make a point of striking up conversations with folks who seemed lost or lonely. Another started to leave early for classes so that she could pick up litter along the way (yes, I have added David Sedaris to her reading list). Heavy Lifting (minimum one hour per month) Speaking for myself, nothing chills my creative vim as efficiently as the cold shadow of an undone task. I mean the kind of thing that never goes away or gets better on its own, but only grows bigger, darker, and scarier, sucking any spare energy into its vortex. (I was about to say that this is especially true of anything that has an emotional component, but on second thought, almost any task that passes its due date will start to carry emotional weight. For example, the need to clean out my crisper drawer currently fills me with a sense of sadness, loss, and thwarted potential.) This task asks you to really level with yourself: what is it that you are avoiding most? And see there! You just looked directly at that horrible thing and are still alive to take the next step: do something about it. It doesn’t have to be a life-or-death matter, as long as taking care of it lets you breathe easier. Over this semester my heavy lifting has run quite a gamut. One month I gritted my teeth and sorted out some issues with the IRS: whew! I also initiated a couple of long-avoided carefrontations with dear friends: hurray! And I did four loads of laundry AND put them away: ahhhhh… Bonus, you eventually learn that it takes less time and effort to just deal with the damn problem than it took to avoid it. Can you think of another arena in which the muscles of decisive action might come in handy? (HINT: YOUR CREATIVE PRACTICE. Oh wait, that was the answer, not a hint. Decisive action in action!) I hope that some of you reading this will find these practices as helpful as I have. If something shakes loose for you, I’d love to hear about it. More Creativity Camp activities and assignments to come… Whenever I’m asked about my favorite medium, I’m tempted to answer…spreadsheets!

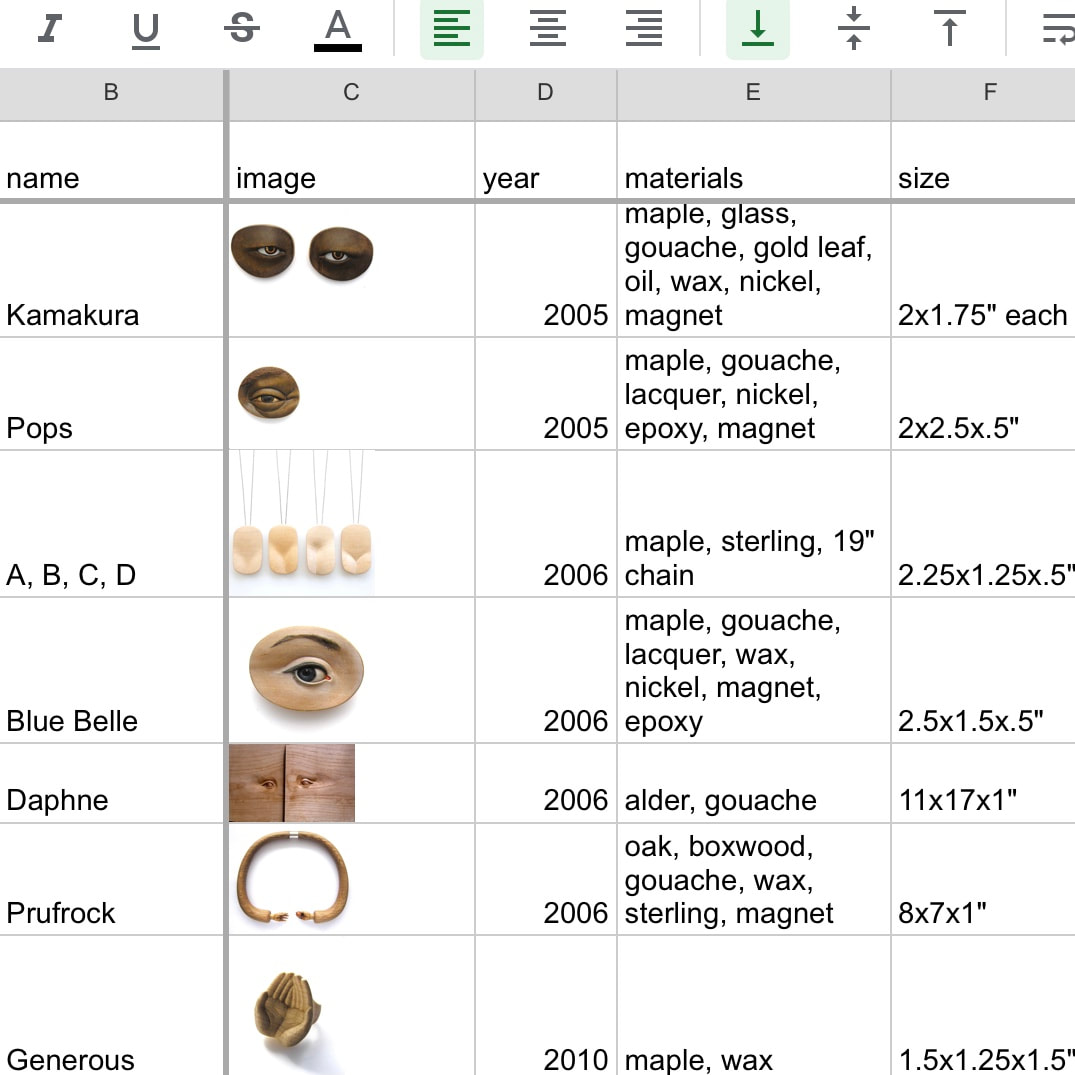

Since I tend to accumulate more information that my memory can handle, I build spreadsheets for almost everything I consider important or interesting. I get a little tingly over formulas and automation, but even a simple sheet is a joy when it does its job well. My Art Log spreadsheet was inspired by my grad school professor, Mary Lee Hu, who urged us to make a regular habit of recording all the salient details of our artwork in one centralized location. Mary kept her own log on a stack of index cards and it worked just fine; when a museum approached her about mounting a retrospective she was able to look in her cards for the details and current location of almost every piece they asked for! I updated her idea into a digitized spreadsheet and even if it never comes in handy for a retrospective, having all this info in one place has shaved hours off of filling out applications (see the “Mise en place” section of my previous post). Don’t yet have a log of your own? Here’s a simple template in Google Spreadsheets that you can use as a starting point. Some of these fields I fill in religiously, others only when relevant:

Of course you can tailor the fields to suit your own needs, but it’s worth making a strict habit of taking a photo and filling in the log whenever a new piece leaves your hands—whatever the reason, whether or not you expect it to come back. When you’re just starting out you may think that you’ll remember how big each piece is, or who bought it, but most of us won’t, and the longer you wait to start keeping records, the tougher it will be. I went to a pathologically competitive middle school. Every action students took was judged and scored, and our tallies were public record. Naturally, participation in sports was by try-out only. Very unnaturally, I decided I wanted to be on a team, despite my total lack of ability.

On the second day of an already lackluster 7th grade softball try-out, a classmate and I were lobbing a ball back and forth in light rain. My glasses fogged up just as a fast, accurate pitch headed straight for my face and I caught it…in my mouth. My lower lip skewered itself on my lower teeth and although my upper front teeth stayed put, the blow killed the nerves and someday they’ll have to come out. I was back at try-outs the next day. I did not make the team. I was back at softball try-outs the next year. I did not make the team then, either. By the end of middle school I had tried out for every team and hadn’t been chosen for a single one. I think about that experience a lot. Of course it was humiliating and public proof of my “loser” status. It launched a lot of tropes about teams and being left out that I still struggle with more than 30 years later. It undermined my childish expectation that adults would be kinder and more just than children. And I have to wonder what might have happened if I had redirected that focus and tenacity towards activities I was actually any good at. But that experience also gave me a valuable skill that probably wouldn’t have come from a childhood of easy success: when absolutely necessary, I can take it in the teeth and come back for more. For a professional artist, resiliency might be even more useful than a facility with color wheels or vanishing points. In my earlier blog post, I talked about the “shadow CV” of rejections that scaffold the public CV of my successes. Here are a few of the practical and emotional tools that have helped me along the way. 1. Get Your Mise en Garde A chef doesn’t chop parsley or make stock every time an order comes in. Nope, they get ready for a shift by pre-preparing all of the ingredients that expect to use most often; the practice of mise en garde lets them work more quickly while having the flexibility to deal with that “special” customer who insists on ordering off-menu. In terms of applying for art opportunities, there are things you will need over and over: a resume, images, references, etc. By anticipating these general needs and preparing accordingly, you can work on individual applications more efficiently, you can better respond to last-minute opportunities, and you give self-doubt less of a foothold. 2. Build a Ladder I try to apply for at least one thing (show, grant, teaching gig, etc) per month, which helps to smooth out both logistical and emotional bumps. My more natural inclination is to do a whole batch of applications when the mood strikes, but then I am likely to have a soul-crushing batch of rejections arriving around the same time (or very rarely, a stack of simultaneous acceptances, which is its own kind of problem). By sending stuff out monthly, I usually get one rejection at a time, and usually by the time it arrives I have the next application out the door; each rejection stings less because I’ve already moved on. 3. Dress for the Job You Want Direct the bulk of your energies towards applications for which you are qualified, but every once in a while treat yourself to a long shot. Sometimes I’ll complete an application for something and not turn it in because I just want to test drive a possible new direction for my work or career. Sometimes I’ll go ahead and turn it in and then pay close attention to how the eventual rejection makes me feel; if “meh,” I redirect my efforts elsewhere, but if I’m really upset I look carefully at the steps I would need to take to be a stronger candidate the next time a similar opportunity comes along. And very occasionally I make it to the interview phase; I’ve never gotten an opportunity for which I was completely unqualified, but I have reaped valuable connections, feedback, and motivation. 4. Audition Amnesia One of my co-teachers at a youth arts camp was a professional hip-hop dancer. He had had a huge career but as he slid into middle age, he was booking fewer and fewer gigs. How did he not just give up and sink into the La-Z-Boy of despair? He had trained himself to forget about an audition the second it ended. He didn’t replay it in his mind and beat himself up about things he could have done differently. He didn’t hover by the phone waiting for it to ring. If it did ring, it was a surprise—maybe a good one, maybe a bad one, but one that hadn’t cost him any unnecessary time or emotional energy. I can verify that amnesia is learnable; I couldn’t tell you the last three things I’ve applied without checking my notes and I’m happier for it. 5. You Already Have the “No” The Listserve was a mailing list of people from all over the world, one of whom was chosen at random to send a message to the entire list each day. One writer shared a nugget of advice that has proved to be the most valuable reframe in my emotional arsenal. She asked her mentor how she, the mentor, managed to remain resilient in a highly competitive field; the mentor said, more or less, “If you don’t try, you already have the ‘no.’” This is similar to the idea that you miss all the balls you don’t swing for in the way it argues for missed opportunities being the default, but it adds a level of agency and emotional nuance. First of all, if anyone’s going to reject me, I’d sure rather it not be me doing the rejecting. Second, when you send out an application, you’re not giving them the chance to reject you; you’re giving them the opportunity to accept you. I hope that something here will be of use to you or to someone you care about! And if you have any strategies that allow your own Weeble to wobble without actually falling down, I would be very happy to hear about them. After all, the rejections won’t stop until I do! 2021

Museum of Art and Design Virtual Artist-in-Residence Jake Rusher Park Public Art Project World Wood Day 2020 2 + U 2nd Ave Lobby World Wood Day City of Issaquah Tibbetts Valley Off-Leash Dog Park City of Durham Pre-Qualified Artist Registry BASE Cohort Bothell Fire Station 42 Artist Trust Fellowship South King County Recycling Center Harris Building Interior Art Tokyo Biennial Haystack Open Studio Residency Jacksonville Medical Lobby Sculptural Installation 2019 World Wood Day Artist Designed Infrastructure Bioretention Edition Seattle Metals Guild Grant 2018 Jakob Bengel Residency 2017 Shunpike/Amazon Residency AJF Grant Bloedel Residency Amara Mural Seattle Center Winterfest 2016 Bloedel Residency Olson Kundig Creative Exchange Jakob Bengel Residency 2015 Seattle Public Utilities Green Infrastructure and Waterways Artist-in-Residence Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship Rome Prize Kohler Residency Artist Trust Fellowship Seattle Airport Concourse 2014 Artist Trust GAP Grant 2013 Artist Trust EDGE Program Houston Center for Craft Residency Appalachian Center for Craft Exhibition Artist Trust GAP Grant 2012 Artbridge Fellowship Artist Trust GAP Grant 2011 Henry Radford Hope School of Fine Arts PIVA 2009 McColl Residency Artbridge Fellowship A few times in my career, another artist has done me the tremendous kindness of pulling back the curtain on a truth that isn’t normally part of polite conversation. There was: the professional artist who spelled out how her pricing formula covers her economic bases and adds an emotional surcharge; the super-successful artist who spoke candidly about the mad paddling it took to keep all her ducks afloat; and the former peer group who listened to my struggles but admitted they couldn’t really identify because they had “married well.” I am so thankful to each of these artists! In each case their honesty and openness helped me to see my own situation with more patience and clarity. I’ve been thinking about these lessons even more frequently since I began to tell people about being a Penland Resident. There has been a tremendous amount of support and enthusiasm, but I’ve also heard and sensed some deflation from people who contrast my little spike of success with whatever’s going on for them. I can feel this deflation second-hand because I’ve so often felt it first-hand, the sense that opportunities are finite and not for me. I’d like to take a turn at pulling back the curtain, so that anyone inclined to comparisons at least has more to work with than the shiny surface of a public achievement. So I’m publishing a list of those times that I swung and missed. I think of it as a “shadow CV,” an inverse of my actual accomplishments without which those accomplishments would not exist. (If you do take a look at it anytime soon, note that I am working backwards through my records, so my shadow CV will continue to grow.) This is not false humility or self-deprecation. It isn’t a “poor me” ploy for sympathy. It’s not my version of “when I was your age I walked fifty miles to the studio and it was uphill both ways.” It isn’t sour grapes. These “failures” are their own kind of achievement and I’m proud of them. If you are also an artist or someone whose career revolves around rejection, there are some great reasons to keep a list of your unsuccessful efforts:

And if you have a shadow CV, there is a great reason to share it with others in your field, particularly those who are getting starting or those who are struggling:

The Windgate ITE Fellowship allowed me to play at both ends of the scale, incorporating my jewelry forms into architectural elements as well as exploring jewelry inspired by furniture and architecture. This brooch is carved from basswood and is based on the fan-like pattern of iris leaves. I'd been thinking about this little guy for a long time, and finally had the chance to figure him out during my Windgate ITE residency. His body is turned dogwood and legs are maple stained with ink and hinged with watchband spring bars. |

|

© 2015 - 2023 Julia Harrison, LLC |